Cranmer’s Immortal Bequest

Thomas Cranmer was burned at the stake March 21,1556 in Oxford England. Some months before the Archbishop of Canterbury was forced to watch bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley suffer the same fate. Eye witnesses reported that Cranmer thrust his right hand deeper into the fire as he burned, signifying his contempt for the recantations of Protestantism which he had previously signed. He died courageously, declaring “Lord Jesus, receive by spirit. I see the heavens open and Jesus standing at the right hand of God.” In Bloody Mary’s five-year reign as Queen some 282 Protestants were killed in a futile attempt to rid the kingdom of the evangelical heresy.

Archbishop Cranmer is the lesser-known of the sixteenth century reformers but, as recent scholarship has shown, he was a first-class thinker alongside the best minds of the Protestant Reformation. Comparatively, he shied from the limelight and he never relishes the hand-to-hand combat with the popes and potentates that seems to have fueled some of the other reformers. He was the quiet rector behind Henry VIII and Edward VI, using “the full powers of his position as Primate of All England to inculcating the Protestant faith into every fibre of English life and law” (Ashley Null).

He was the most important theologian of the English Reformation, and arguably the most important in the five hundred year history of the Church of England if, for no other reason, he was responsible for all the recognized formularies of our Anglican heritage: the Articles of Religion, the Homilies (of which he wrote four of the original twelve in the first book), and the Book of Common Prayer (including the Ordinal). In so many ways it it fair to call this “Cranmer’s Church.”

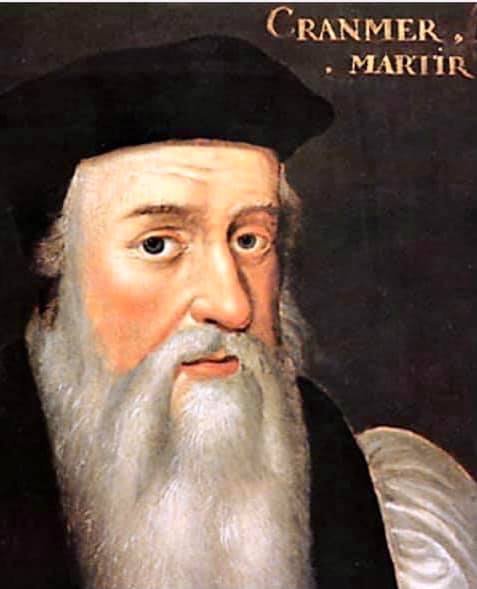

There are two surviving contemporary portraits of Cranmer which betray his complexity and two very different stages of his life and ministry. The first, by Gerlach Flicke is now in the National Portrait Gallery, London, shows the clean-shaven primate in 1545. The second is by an anonymous artist and it hangs in Lambeth Palace, and dates to the time he grew his beard at the beginning of Edward VI’s reign. Cranmer died at the stake with a long beard which is dramatically depicted in the engravings in Foxe’s Acts and Monuments in various editions. Clergymen wearing beards meant only one thing at the time: protestant! And when Cranmer grew his in 1547 he was announcing to the world that he was rejecting the old church for the new. Cranmer may have started out a dignified humanist and Henry’s obedient Archbishop, but he ended his life and career as a convinced Protestant completely in sync with the Continental Reformation of Henrich Bullinger, Peter Martyr, and Jan Laski.

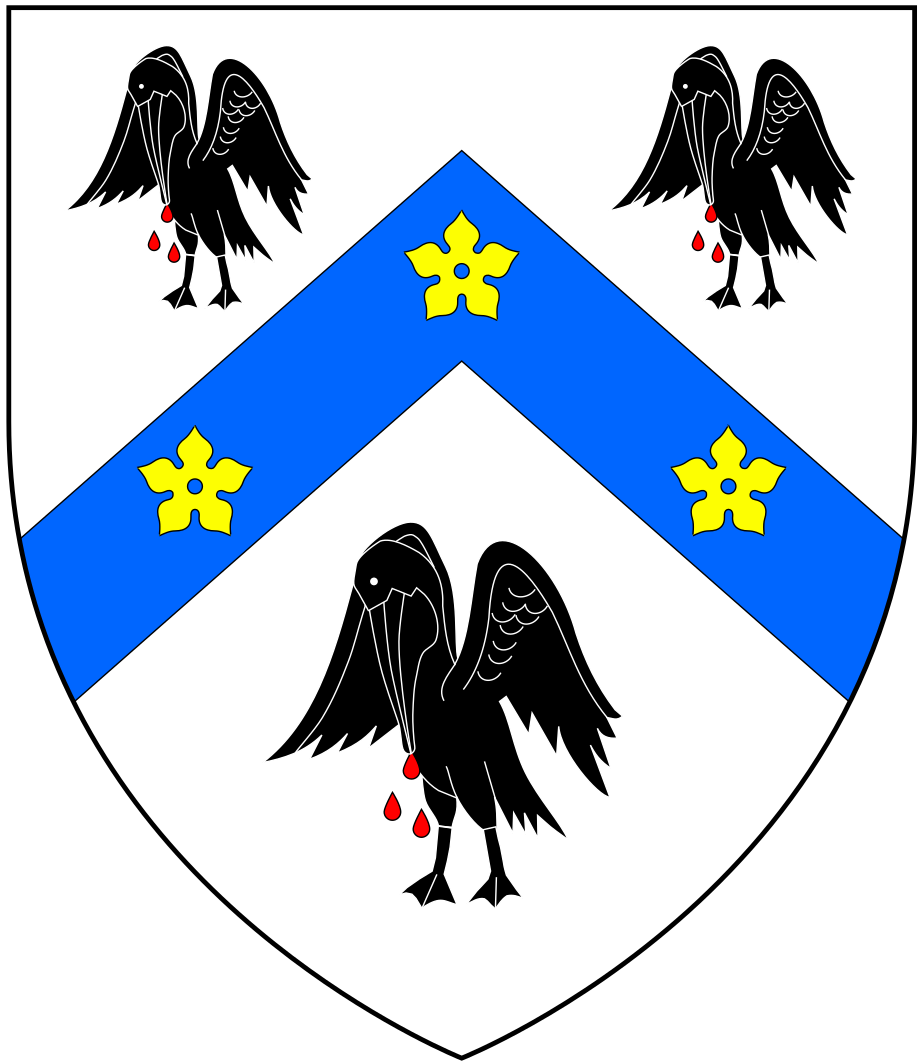

King Henry VIII changed Cranmer’s family shield from cranes to pelicans, declaring to him that pelicans should signify to him “that he ought ‘to be ready, as the pelican is, to shed his blood for his ‘young ones, brought up in the faith of Christ’” (John Strype, an early Cranmer biographer, 1694). The legend of the pelican is significant and beautiful: that in a time of famine, the mother pelican wounds herself, striking her breast with her beak to feed her young with her own blood, and in turn loosing her life. On Thomas’ coat of arms is the gospel: Jesus did not regard equality with God a thing to be grasped, but he emptied himself, even to death on the cross, so that every knee will bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord (Phil 2).

Thomas Cranmer: A Life, Diarmaid MacCulloch

The Boy King: Edward VI and the Protestant Reformation, Diarmaid MacCulloch

“Judging the English Reformation,” Diarmaid MacCulloch

Thomas Cranmer’s Doctrine of Repentance, Ashley Null

“Thomas Cranmer’s Reputation Reconsidered,” Ashley Null, Reformation Reputations: The Power of the Individual in English Reformation History, Ed. David J. Crankshaw and George W. C. Gross

Archbishop Cranmer’s Immortal Bequest, Samuel Leuenberger

“Thomas Cranmer’s Reading of Paul’s Letters” Ashley Null & “The Texts of Paul and the Theology of Cranmer” Jonathan A. Linebaugh, Reformation Readings of Paul: Explorations in History and Exegesis, Ed. Michael Allen and Jonathan A. Linebaugh